Summary

Game outline

How the game works

The Nash equilibrium

How to escape Bertrand competition

Real life examples

Limitations of Bertrand Competition

Bertrand Competition -

How Firms Compete on Price

The Bertrand competition, a game theory model, illustrates a race to the floor towards marginal cost. Typically, competitive pricing strategies include loss leaders, premium pricing and price matching strategies, however in the Bertrand competition model, it assumes goods are homogenous and firms choose prices simultaneously: where price is their only strategic choice. Firms can price above marginal cost, but there’s the possibility a competitor will undercut and steal the entire market. This intense price competition occurs because there is little way for companies to differentiate their products, so the only way to gain a competitive edge is through simple pricing strategies which undercut any other strategy. (Fiveable) Thus, the aim in the Bertrand competition model is to undercut competitors to capture market share. This undercutting repeats until the mutual best response, that is, the Nash equilibrium is found, whereby the price is stable and sustainable. The Nash equilibrium leads to a situation where the price equals the marginal cost (p = MC), resulting in low profits for firms compared to other competitive models like Cournot competition. The Bertrand game occurs in duopolies and oligopolies, examples include same destination airline tickets and identical gas stations. (Salish) The Bertrand competition model does have some limitations, as noted at the end.

6 Minute Read

Rundown

In the Bertrand Game, two firms simultaneously choose the price (p) that presents the best response to the competitor’s price, competing for a single buyer. The one product they are producing and pricing is homogenous and costs (c) to produce. They are competing for the one buyer through their pricing strategy (market share), and the buyer purchases the goods from the firm who sets the lowest price, a key difference to Cournot Dupoly (in which the firms compete in quantity produced).

If the buyer purchases the product from a firm, the firm produces it with a cost of c.

If both firms set the same price, the buyer selects one firm at random.

Since each firm can choose any price, each firm’s set of strategies is 0 to -> infinity.

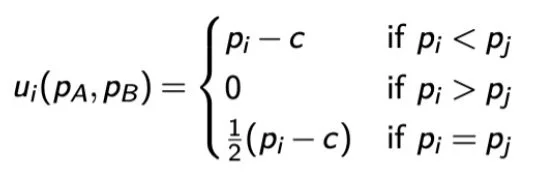

The payoff function:

The Game

pi < pJ means pi wins the sale, and therefore gets to produce the good at pi - c (price - cost)

pi > pJ means pi loses the sale, and therefore receives 0.

Pi = pj means both firms split the sale, so it’s profit is ½ (pi - c).

Let’s play this game and find the Nash equilibrium.

This application of the Bertrand game is from Suzuki (2025), my game theory lecturer.

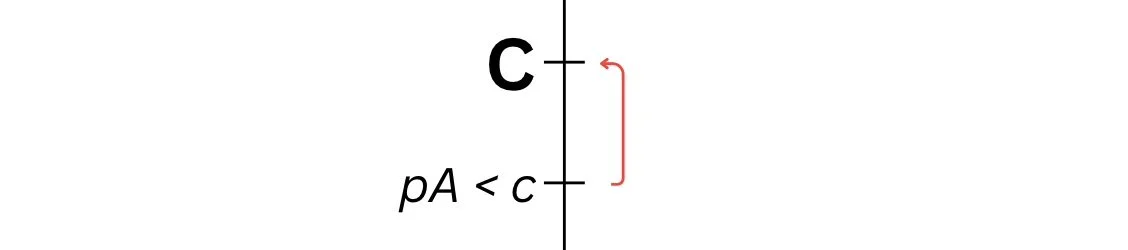

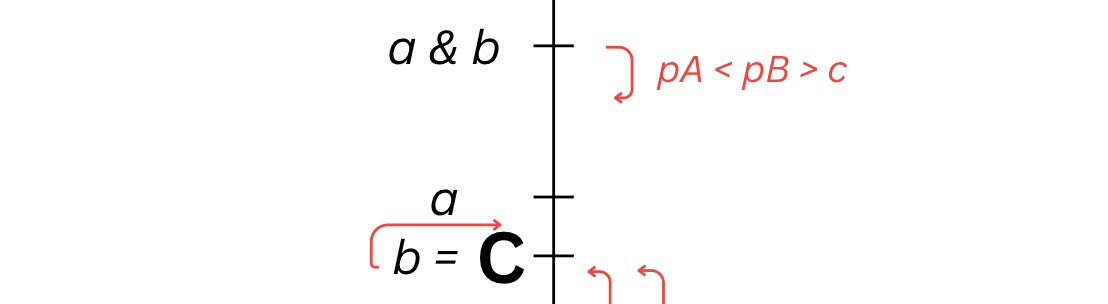

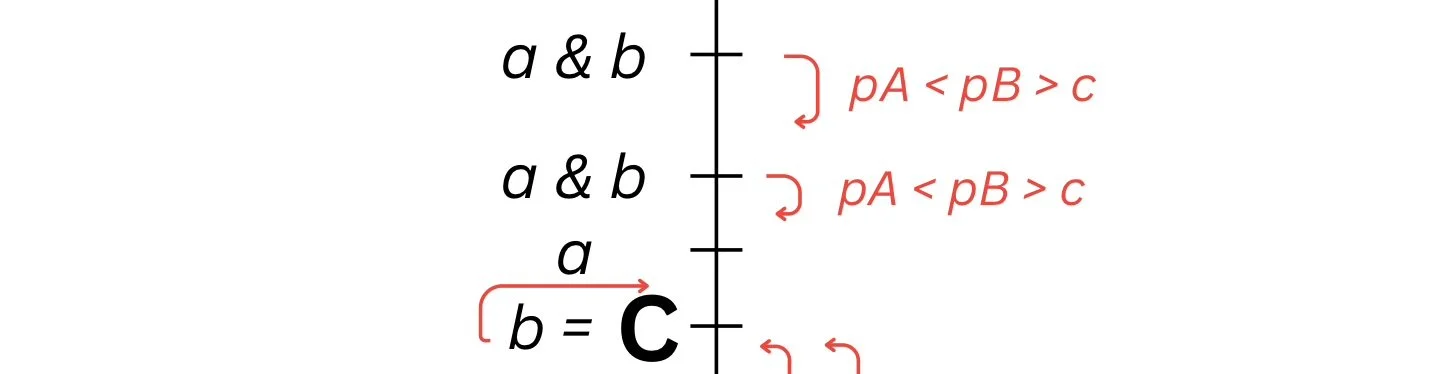

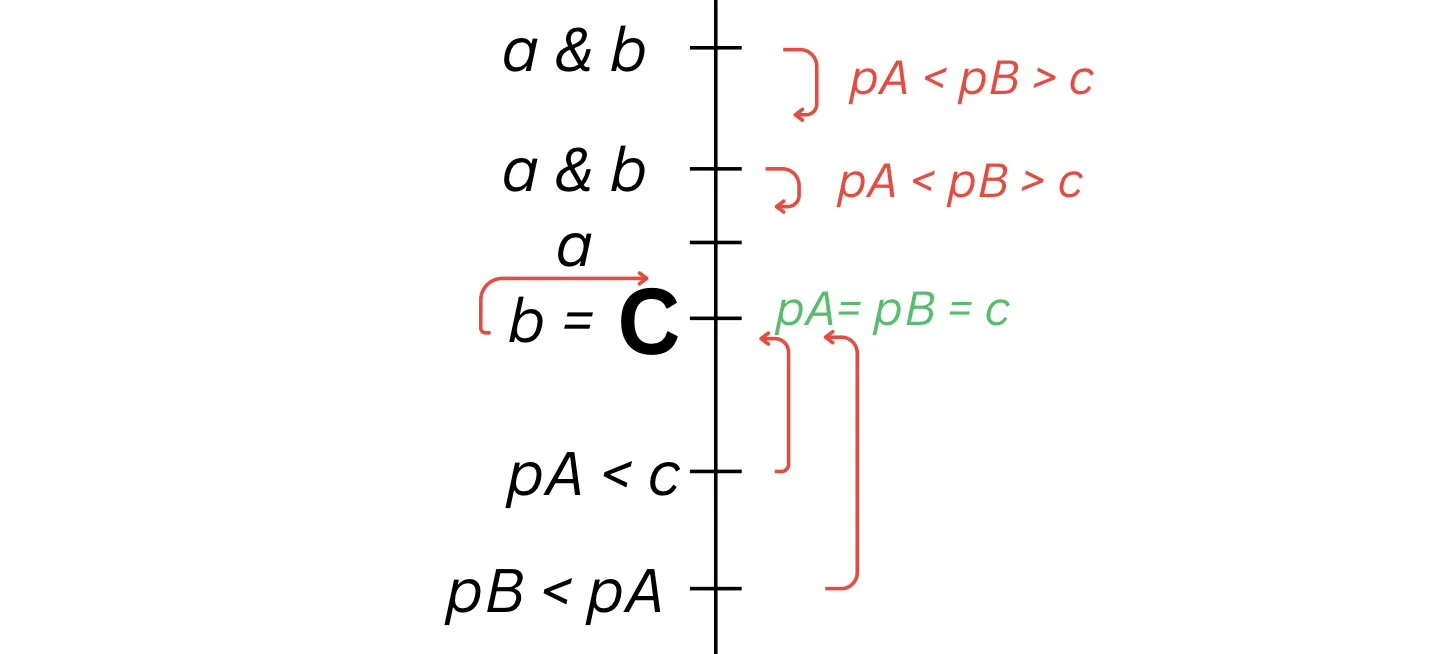

No Nash Equilibrium When Price is Set Below Cost

There is no Nash Equilibrium when price is set lower than cost (p < c) because a firm will simply deviate, as seen below:

1) a firm can decide to price its goods below cost, but it will earn a negative profit, and therefore deviate to pricing its goods at least equal to cost, pi = c

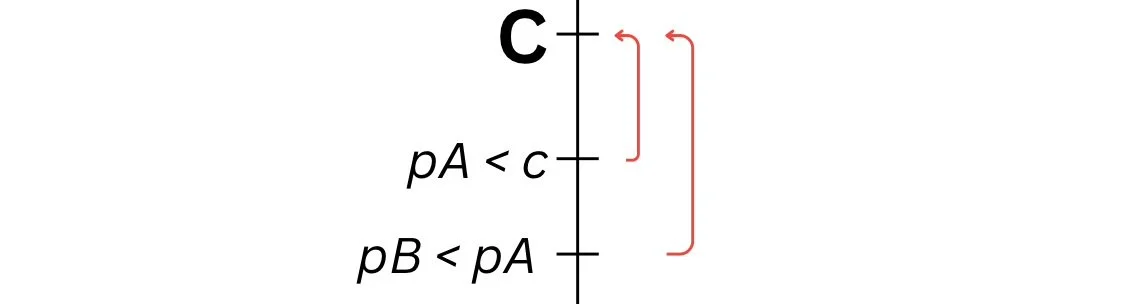

2) a firm can price its goods below cost, and another firm could undercut it, but this is irrational: it will earn negative profit. The firm would deviate and price its goods at least equal to cost, pi = c, even if that means pricing its goods above the other firm.

No Nash Equilibrium When Price is Set Above Cost

There is no Nash equilibrium when both firms have their prices set above cost,

pA > pB ≥ c, because:

1) a firm will deviate and undercut the other firm, guaranteeing the sale of their goods.

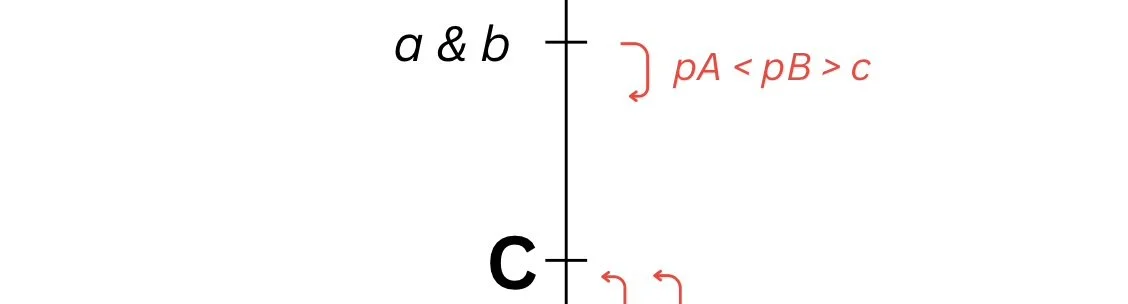

2) if pA > pB = c both firms earn nothing because: customers don’t buy from firm A, and instead buy from firm B who is earning nothing (pB = c). But if firm B deviates by slightly raising its price above C (whilst still below firm A’s) both firms earn profits and split the market as some customers may be price inelastic with firm A and some will be more elastic and buy from firm B.

If pA = pB > c then firm A’s profit is ½ (pA - c)

But firm A could price its goods between cost and its original price (eg.: set its price below firm B but above C): it would be incentivised to do so as pA - c is greater than ½ (pA - c), meaning this outcome is not stable and not the Nash equilibrium.

Another Strategy Profile

The Nash equilibrium: the stable, sustainable outcome is pA = pB = c. Each firm gets 0.

If a firm deviates to a higher price, the firm gets 0

If a firm deviates to a lower price, the firm gets a negative profit.

Thus, there is no incentive to deviate. This is the Nash equilibrium.

The Nash equilibrium

How To Escape Bertrand Competition

When product differentiation is introduced, as is in reality with non-homogenous goods (so most goods), which include strategies like loss leaders, premium pricing or price matching, firms can escape the zero profit equilibrium. (Investopedia) This shift allows for higher profit margins, allowing companies to focus on innovation, “highlighting the importance of non-price competition in altering market dynamics.” (Fiveable)

As explained by Salish (2021) on Inomics, an example of Bertrand competition is the market for petrol: as petrol is a homogenous good, and there are many competitors (assuming the petrol stations in question are next to each other, otherwise the good is heterogeneous), consumers buy from the cheapest seller. Thus it is difficult for petrol companies to use competitive pricing strategies to differentiate the product they’re selling. This leaves companies to undercut in price, even by a cent to capture demand. This drives prices towards marginal cost, and hence profit margins become razor thin!

Real Life Examples

Limitations of Bertrand Competition

Per Tejvan Pettinger (2017), some limitations of Bertrand competition include:

1) in a duopoly, firms should be able to make high profits. “It depends on the degree of barriers of entry.”

2) The Bertrand game assumes companies are seeking to maximise sales, but some might be trying to maximise profits.

3) consumer choices are not always limited to just choices: factors include brand loyalty, convenience, ease of purchase and quality of the good

4) consumers don’t always have perfect information about the cheapest goods (although, this is changing in the information era)

5) there may be search and transaction costs of moving to a cheaper product

6) it is rare goods are homogenous

References

Fiveable. (2024, August 1). Bertrand Competition – Game Theory. https://fiveable.me/key-terms/game-theory/bertrand-competition

Investopedia. “Competitive Pricing: Definition, Examples, and Loss Leaders.” Investopedia, 30 July 2020, www.investopedia.com/terms/c/competitive-pricing.asp.

Salish, Mirjam Sarah . “Bertrand Competition.” INOMICS, 5 Jan. 2021, inomics.com/terms/bertrand-competition-1504578.

Salish, Mirjam Sarah . “Bertrand Competition.” INOMICS, 5 Jan. 2021, inomics.com/terms/bertrand-competition-1504578.

Suzuki, Toru. “Application of Nash Equilibrium to Various Games.” 2025.

Tejvan Pettinger. “Bertrand Competition | Economics Help.” Economicshelp.org, 28 Nov. 2017, www.economicshelp.org/blog/glossary/bertrand-competition/.