Image source: Unsplash u/hang Shang

Fixed Rate Bonds: basics

Liam Scotchmer

References listed below.

Summary/Intro to Bonds

If you want to buy a house, you likely need to get a loan from a bank - once you have the loan, you make partial payments on top of interest to the lender (the bank).

A bond is similar to a loan, however the lender/borrower situation is reversed - you are the lender, and it is a firm or a government that is the borrower. Additionally, bonds can be traded.

For example, the firm or government issues debt, called a bond, and you buy the bond. You are now a bondholder. You pay the market price, but will receive its face value at maturity (this will make sense later on). Additionally, you, the bondholder, will receive regular interest payments from the bond issuer.

The bond can then be traded before maturity.(Reserve bank of Australia 2022).

This blog was written using a combination of articles written individually by James Chen, Nick Lioudis, Jon Fernando and Claire Boyle-White all from Investopedia (different dates), EconplusDal (YouTube, 2017), an article from the Reserve Bank of Australia (2022), one from HKT Consultants (2021) and an article by Analyst Notes (2025).

4 Minute Read

According to EconPlusDal (“Bonds and Bond Yields,” 2017) a fixed rate bond has four important components:

Coupon rate - is a fixed annual interest rate the bondholder will be paid (influenced by market interest rates)

Maturity - how long until the bondholder receives their full principal back (Fernando 2022)

Nominal(face) value - is the amount the bondholder receives at maturity. This is fixed.

Market price - this is what matters a lot- this is what is paid for the bond.

But how does the trade of bonds work? Let’s start from the beginning.

How do bonds work?

Put as simply as I could:

Government/firm issues a bond with a coupon rate (interest rate) similar to the market interest rate.

Primary market: when an investor has purchased the bond for the first time, this is called buying in the primary market. RBA (2022) (An aside: This first price of a bond depends on many factors like the coupon rate, term of bond, and price of similar bonds).

In the primary market, according to Chen (2025) the bondholder pays an amount close to the face (nominal) value of the bond, either at par (= to face/nominal value), at a discount or premium… this is dependant on market rates.

Using an example from Analysts Notes (2025)“A 1-year, semi-annual-pay bond has a $1,000 face (nominal) value and a 10% coupon (return).”

- “At a market rate of 8%, the bond value is $1,019 (premium)” (bond is selling at a premium because the coupon rate > market rate… there are many buyers pushing up the price. And yield (return) is 9.81% (smaller return than discount and par because this bond costs more to buy)

- “At a market rate of 10%, the bond value is $1,000 (par)” (bond value is equal to face value because coupon rate = market rate. And yield is 10% because at par, face value = coupon rate)

- “At a market rate of 12%, the bond value is $982 (discount)” (bond is selling at a discount because coupon rate < market rate. There are few buyers wanting to buy this bond. And yield is 10.18%, that’s higher than premium and par because bond was bought cheaply, so more earnings.. makes sense).Okay, so now we understand that the bondholder has either bought the bond at par, premium or a discount, ( which is dependant on the market rates and other factors). The bondholder can keep the bond until maturity and earn the face value, or they can sell now (due to many reasons). If the bondholder decides to sell the bond before maturity it will be sold on the '“secondary market.”

In the secondary market - bond market price fluctuates on top of the face value again like it did earlier.

Remember:

When market prices exceed the face value of a bond, bondholder is paying at a premium.

When market prices are below face value of a bond, bondholder is paying at a discount.

When market prices equal face value of a bond, bondholder is paying at par.The new bondholder looking to buy will need to recalculate the yield (rate of return) because market prices have changed. This is done using the current yield formula = annual coupon payment / market price x 100

I am repeating myself a lot, but once more:

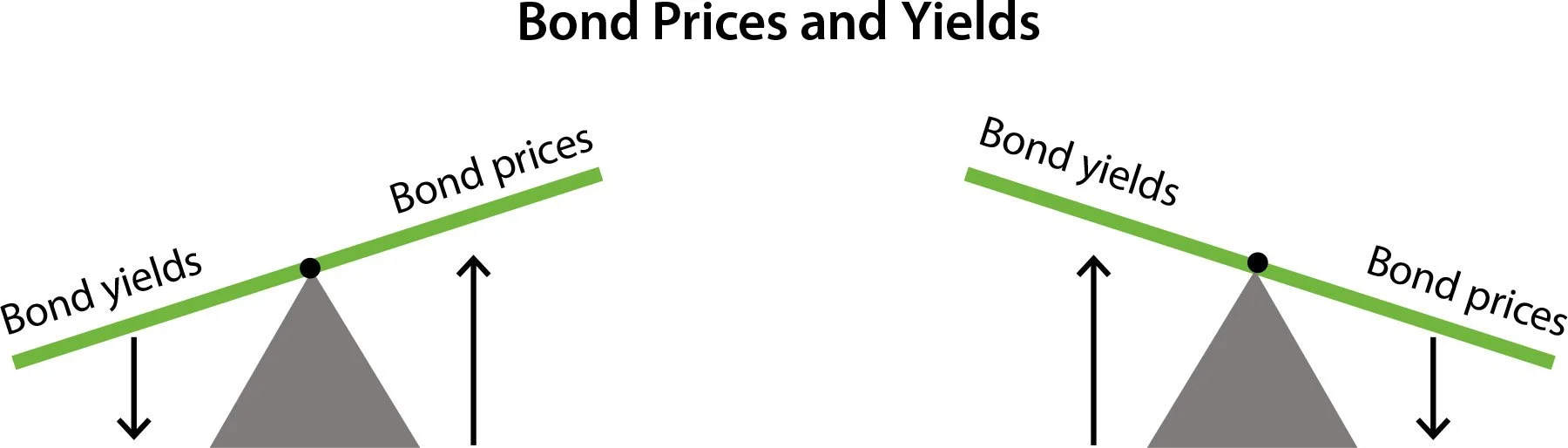

The relationship between the market price and bond yield is inverse. (EconplusDal, 2017)

Source: (Reserve Bank of Australia, 2022)

When prices rise, yields fall.

When prices fall, yields rise, like we saw earlier…What you now need to know now is what happens to prices of bonds and bond yields if the coupon rate on them is higher or lower than market interest rates.

According to EconplusDal (2017)Coupon rate > market interest rate = more demand = higher bond price = lower yield. This happens until yield closely aligns market interest rates.

Inversely, coupon rate < market interest rate = less demand = lower bond price = higher yield. This happens until yield closely aligns market interest rates.

Nevertheless, the bond value will always equal the face value eventually, at it reaches maturity, since that is what the issuer owes. (EconplusDal, 2017)

This is shown below.

Continuing on with Analyst Notes’ article (2025), the value changes as it moves closer to maturity as you can see in this graph… eventually meeting back at face value - because the face value is what is owed by the issuer at maturity, and NOT the market price!

Par = face value aka equilibrium

Market price < face value

Market price > face value

- IMPORTANT CAVEATS:

Risks of owning a fixed rate bond

As we have just seen, because there is an inverse relationship between interest rates and bond prices, there is risk involved. The risk is apparent when market interest rates increase “making an investor’s existing bond less valuable'.” (Chen 2021). If this is confusing, here’s some examples, with the help of Investopedia (Chen 2021).

For example,

-> bondholder buys a bond that pays a fixed annual interest rate (coupon rate) of 5%,

-> but the market interest rate increases to 7%

two things happen:

1) the price of their bond decreases, so if they decide to sell it may be at a loss

2) they will miss out on the higher interest rate

Inversely,

-> bondholder buys a bond that pays a fixed annual interest rate (coupon rate) of 5%,

-> but the market interest rate decreases to 3%

two things happen:

1) the price of their bond will increase, so if they decide to sell it will be at a gain

2) they will have a higher interest rate than others! Yay!

(Chen 2021)

- FINAL: OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Continuing on with Investopedia’s article (Chen 2021):

1) shorter bond terms for fixed rate bonds are less risky*

*However, they will earn a lower interest rate than longer term fixed rate bonds

2) If the bondholder does decide to not sell before maturity, they “will not be concerned about possible fluctuations in interest rates.”

3) The real interest rate = nominal - inflation, so if inflation rises over the duration of the bond term, the purchasing power will lower.

4) if investors believe a bond’s yield won’t keep up with inflation, its price will decrease (less demand for it)

5) It is better to buy bonds when interest rates are high because the companies and governments issuing them must pay a higher yield “to attract investors".”

Let’s put what we’ve learned into play…

Lower market interest rates = higher demand for bonds = higher bond prices = lower yields

Higher market interest rates = lower demand for bonds = lower bond prices = higher yields

This figure from HKT Consultants (2021) shows a decline of bond yields after ~around 2009.

Because yields dropped, it means higher bond prices due increased demand as interest rates dropped.

1) Interest rates must have been lowered

2) Therefore, investors took to bonds and bought more

3) This drove the price up for bonds

4) Accordingly, bond yields dropped (because higher bond price = lower yield)

REFERENCES

Fernando, Jason. “Bonds: How They Work and How to Invest.” Investopedia, 3 May 2024, www.investopedia.com/terms/b/bond.asp.

Lioudis, Nick. “The Inverse Relationship between Interest Rates and Bond Prices.” Investopedia, 15 Oct. 2024, www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/why-interest-rates-have-inverse-relationship-bond-prices/.

HKT Consultant. “How Bond Prices Vary with Interest Rates – HKT Consultant.” Phantran.net, 23 June 2021, phantran.net/how-bond-prices-vary-with-interest-rates/. Accessed 27 Sept. 2025.

Chen, James. “Bond Discount.” Investopedia, 29 May 2021, www.investopedia.com/terms/b/bond-discount.asp.

EconplusDal. “Bonds and Bond Yields.” YouTube, 11 Mar. 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=_OwppAqFPIw. Accessed 2 Feb. 2025.

Reserve Bank of Australia. “Bonds and the Yield Curve.” Reserve Bank of Australia, 2022, www.rba.gov.au/education/resources/explainers/bonds-and-the-yield-curve.html.

Boyte-White, Claire. “Bond Yield Rate vs. Its Coupon Rate.” Investopedia, 2019, www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/051215/what-difference-between-bonds-yield-rate-and-its-coupon-rate.asp.

Chen, James. “Fixed Rate Bond Definition.” Investopedia, 31 Mar. 2021, www.investopedia.com/terms/f/fixedrate-bond.asp.

Analystnotes.com. “2025 CFA Level I Exam: CFA Study Preparation.” Analystnotes.com 2025, analystnotes.com/cfa-study-notes-relationships-between-bond-price-and-bond-characteristics.html. Accessed 27 Sept. 2025.