This article is based on an educational sheet from the Reserve Bank of Australia (n.d) linked below.

Bond Yields

Bond Prices and Yields

The Yield Curve for government bonds

The Level of The Yield Curve

The slope of The Yield Curve

Normal yield curve (shown below)

Flat yield curve (shown below)

Deep dive: Why is the Yield curve important?

Central to transmission of monetary policy

Investor’s expectations

Liam Scotchmer

References listed below.

Intro

A bond is an IOU issued by a government or firm and purchased by any individual or firm called a bondholder. It is essentially a loan, except the borrower/lender situation is reversed.

In return, the bondholder receives the principal (amount lent) at maturity, and in the interim: receives interest payments called coupon rates. Additionally, the bondholder can trade their bond with other investors, creating a market… and we all know what markets mean: that prices are determined by the forces of supply and demand! Thus bonds vary in price at issuance and from issuance. (RBA, n.d.)

This is illustrated below.

3 Minute Read

The price of government bonds fluctuate: either at par, discount or premium, and in both the primary market (at issuance) and especially in the secondary market (where investors trade bonds). Therefore, investors use the yield to maturity (YTM) formula to calculate how much they expect to receive until the date of maturity (RBA n.d.) It accounts for changes in prices.

Things to note:

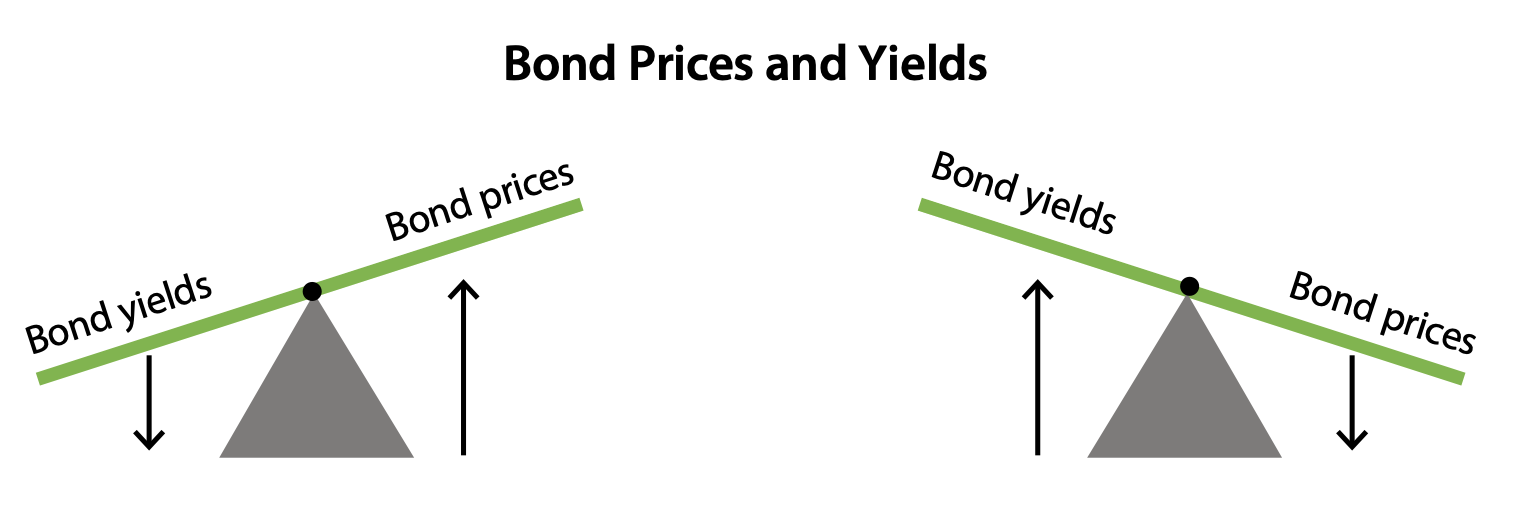

Now combining prices and yields:

Bond prices and yields are inverse.

-> Bond price up -> yield down

-> Bond price down -> yield up

Source: Reserve Bank of Australia | Education

An aside: The reason the prices of bonds fluctuate is mainly due to changes in the coupon payments of similar bonds with similar maturities/credit rating (like the RBA benchmark rate linked here) or the cash rate set by the Reserve Bank linked here.

For example:

-> Cash rate increased to 4% -> old bonds at 3% lose value because investors don’t want them/can seek better returns elsewhere, thus it’s price decreases until the YTM aligns closely with the new cash rate.

-> Cash rate decreased to 2% -> old bonds at 3% increase in value because investors want them/they have better returns than elsewhere thus it’s price INCREASES until the YTM aligns closely with the new cash rate.

In summary: you can see that bond prices and bond yields are inversely related.

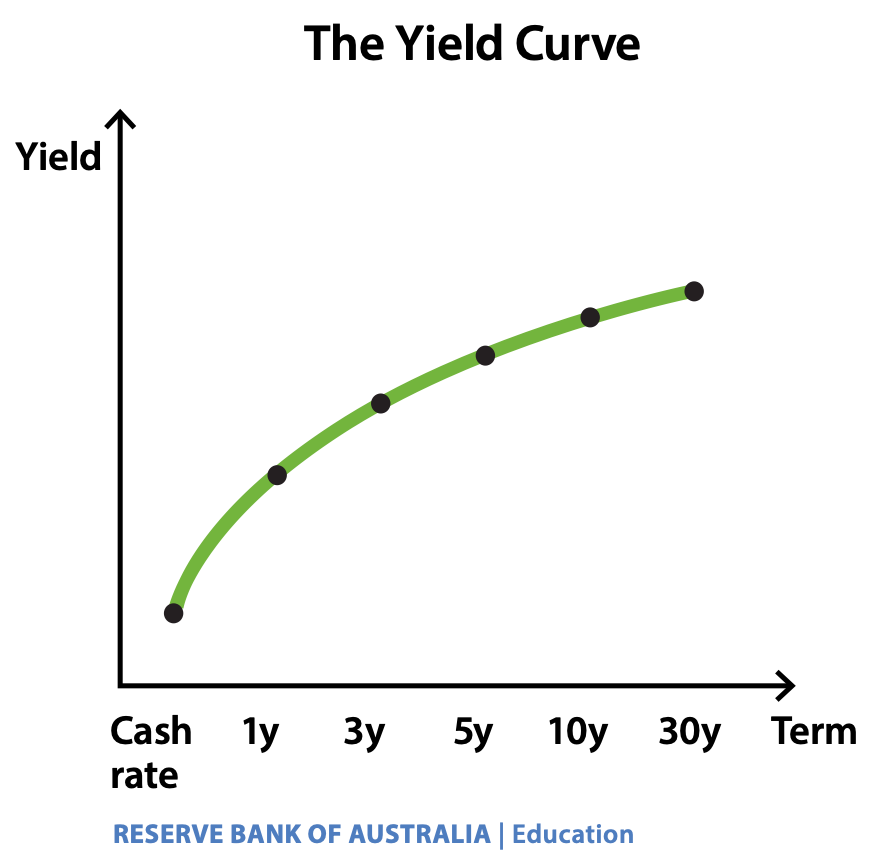

The yield curve is shorthand expression for the yield curve for government bonds.

According to the Reserve Bank of Australia (n.d.), the yield curve “shows the yield on bonds over different terms to maturity.”

Take a look at it: it is quite simple. It is graphed by plotting the yields on the y axis for bonds and at different maturity dates on the x axis (1y, 3y, 5y, 10y, 30y). Because it goes from short term, to long term, the cash rate (shortest term IR) in Australia is the beginning of the curve.

According to the Reserve Bank of Australia (n.d.) there are two “mains aspects of the yield curve that determine its shape:

the level and the slope.

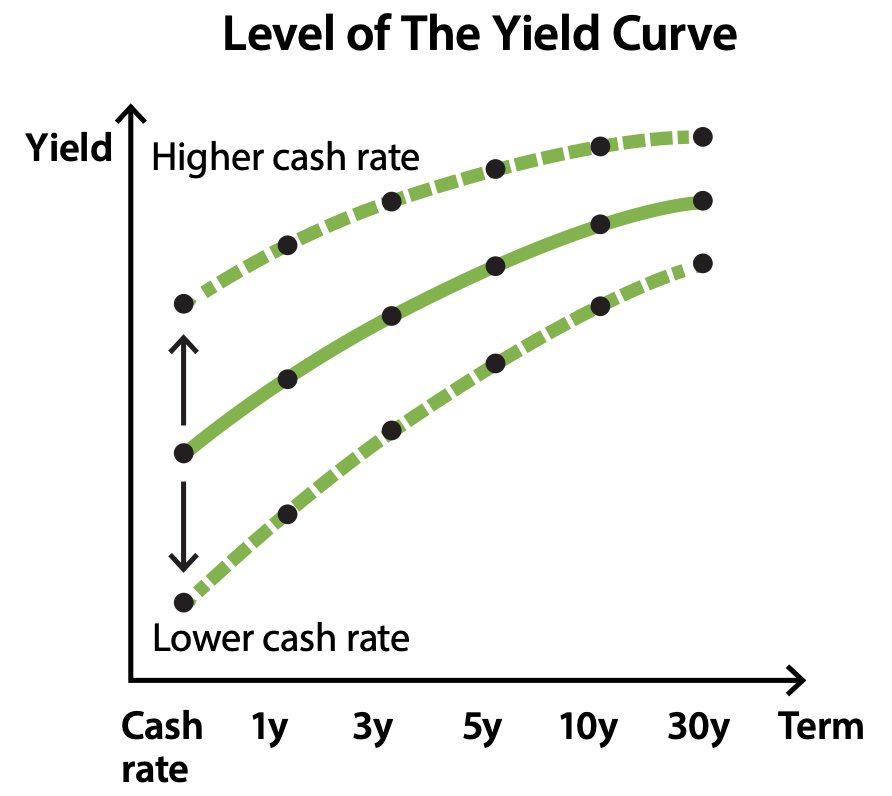

The level is simple: “it’s determined by the interest rates in the economy” This is because it’s referred to as the “anchor” for the yield curve (well of course, it is the first thing to be plotted). The level changes up and down depending on the interest rate (shown below)

Because there’s uncertainty about what the cash rate or inflation will be in the future, there are differences in yields between short term bonds (1y) and long term bonds (10y). This is shown in the slope of the yield curve.

This is considered the normal shape for the yield curve, where the shorter term bonds have a lower yield than longer term bonds. Longer term bonds provide a higher yield, because as we said previously, there is more uncertainty around them - interest rates or inflation could rise.

— When does a normal yield curve occur?

A normal yield curve is “often observed in times of economic expansion, when economic growth and inflation are increasing” because during expansion expectations of inflation are higher so interest rates are anticipated to be increased. (RBA n.d.)

An inverted yield curve is where “short term yields are higher than long term yields, so the yield curve slopes downward.” (RBA n.d.)

— When does an inverted yield curve occur?

It occurs when investors think that the future policy interest rate will be lower than the current policy interest rate. (RBA n.d.)

Inverted yield curve (shown below)

”A flat shape for the yield curve occurs when short term yields are similar to long term yields.” (RBA n.d.)

— When does a flat yield curve occur?

It occurs when the yield curve is “transitioning” between a normal and inverted shape and vice versa. (RBA n.d.)

According to the Reserve Bank of Australia (n.d.) the yield curve is an important economic indicator because of three reasons

The yield curve is considered the benchmark “risk free” yield curve, where interest rates for mortgages, costs of borrowing for businesses or banks and term deposits are added on top of the yield for this curve.

For example, say you take out a fixed rate 2 year mortgage - the bank will look at the yield for a bond maturing at 2 years and see a number; let’s say 3.5% - they will add on an additional percentage to cover costs, profit, and to compensate for risk of default by by borrower. As you can see here, the yield curve at a specific maturity date is the benchmark for other interest rates.

Or if you take out a variable loan, the cash rate will be very important to you. (the first dot on the graph)

Or if the government or a firm borrows for 5 to 10 years, they will look at the benchmark rate for a bond maturing in 5 to 10 years. (4th and 5th dot on graph).

Investor’s expectations

According to the Reserve Bank of Australia, (n.d.) a normal, inverted or flat curve provides insight into what investors expect the future interest rates and inflation to be.

For example: if investors believe there will be inflation, they will also expect policy interest rates to rise, so the curve will shift upwards and look “normal.”

Bank profitability! The slope and level of the yield curve affects the returns banks receive. It is important for banks to be porfitable, as without them credit wouldn’t be available which is “an important factor for economic growth and in particular for investment.” (RBA n.d.)

How it works:

-> Banks earn profits from lending funds at higher interest rate than they pay to borrow funds

- banks earn profit from lending funds at a higher invest rate than they pay to borrow funds from depositors and other sources

banks lend for longer terms than they borrow

profit comes from the difference between long term and short term interest rates (slope curve)If the yield curve is normal (all else equal)

For example, if policy interest rates (set by RBA) are increased, the yield curve will shift upward, and will look normal. The yield shown at maturity for 1y will be low, so for firms/governments/households borrowing short term, their interest rate will be lower. However, for firms/governments/households borrowing at longer terms, their interest rates will be higher (because more uncertainty).

Other notes from the Reserve Bank of Australia’s article:

The yield curve for government bonds is also called the risk free yield curve because government bonds are considered to be safe and default risk free.

The yield for corporate bonds are generally higher than government bonds because they are considered riskier.

Reserve Bank of Australia. “Bonds and the Yield Curve.” Reserve Bank of Australia n.d.

https://www.rba.gov.au/education/resources/explainers/pdf/bonds-and-the-yield-curve.pdf?v=2025-09-30-18-30-27

Fernando, Jason . “Yield to Maturity (YTM).” Investopedia, 2022, www.investopedia.com/terms/y/yieldtomaturity.asp.